10. Fish Stress: What is it and How to Prevent it

You hear it from shopkeepers so often it has almost become trite. It would seem that every problem you have with fish is caused by something called ‘stress.’ You may even think it’s an excuse shopkeepers simply fall back on for unexplained fish loss. Although your dealer may not elaborate further, most of the time stress is the contributing factor in fish illness and death.

Let’s explore this phenomenon and find ways to alleviate it.

What is fish stress?

All organisms throughout the animal and plant kingdoms are acted upon by stress. Survival, in ‘normal’ circumstances, depends on the ability to adapt to and overcome a certain level of environmental and social stress. In stressful situations, the strong survive and the weak succumb and may eventually die.

A number of criteria must be met by the individual in order for the species to survive. These criteria are usually very specific and unforgiving. The absolutes are obvious: food, nutrition, water quality, predators, mating, etc.. Sometimes the factors that contribute to stress are less obvious: territory disputes, pollution, light, sound and temperature. These factors may lead to disease and fish loss.

Think of it as environmental pressure. Like other animals, fish are subject to physical, biological, chemical and social pressures and to survive they must adapt to these pressures. Unable to temper its environment, fish must adjust to it. In its natural living situation, a fish has adjusted to the normal pressures of that particular situation – water quality, available food, type of food, social pressures from its own species as well as other species occupying the same habitat and breeding pressures. When relocated to a captive environment, fish frequently exhibit typical symptoms of stress, such as, lethargy and disorientation, hiding, thrashing, hanging near the surface, and refusing food.

Stress initiates a physiological reaction to changes in environment. In its natural setting, the fish has adjusted to the pressures of its existence and has adjusted to these pressures to become a successful inhabitant of that particular area. Once subjected to changes in that environment, in order to survive, the fish must make immediate adjustments.

Faced with danger, the animal exhibits a confrontation or avoidance reaction, the classic fight or flight response. What happens during the fight or flight response? Some of the response is similar to that of land animals, but much of it is specific to animals that inhabit an aquatic environment. Both fight and flight require a quick burst of energy which is triggered by the release of hormones that begin the rapid metabolism of sugars stored in the liver, which trigger an increase in blood sugar. Blood pressure increases, respiration increases and there is a rush of red blood cells into the bloodstream to carry oxygen to large swimming muscles and to a now rapidly beating heart.

All of these reactions normally initiate an inflammatory reaction, or swelling, which is suppressed in fish by adrenaline released from the adrenal glands. Unique to fish is the regulation of water into and out of the body during the flight or fight response. Under the stress of confrontation, freshwater fish absorb too much water and saltwater fish lose too much. The rapid metabolism of sugar reserves provides additional energy to overcome this fluid imbalance.

What is the result of prolonged stress?

In its normal environment, a fish may exhibit the fight or flight response hundreds of times each day. The confrontations begin quickly and end quickly and the fish’s metabolism has time to recover and prepare for the next confrontation. But what happens when the stress reaction is protracted over a long period of time? Capture, removal from its natural surroundings, tanking with unfamiliar inhabitants, different water conditions, light, sounds and temperature all bring on a prolonged stress reaction that can exhaust all the fish’s reserves, bring on disease and eventually lead to death.

What role does stress play in disease?

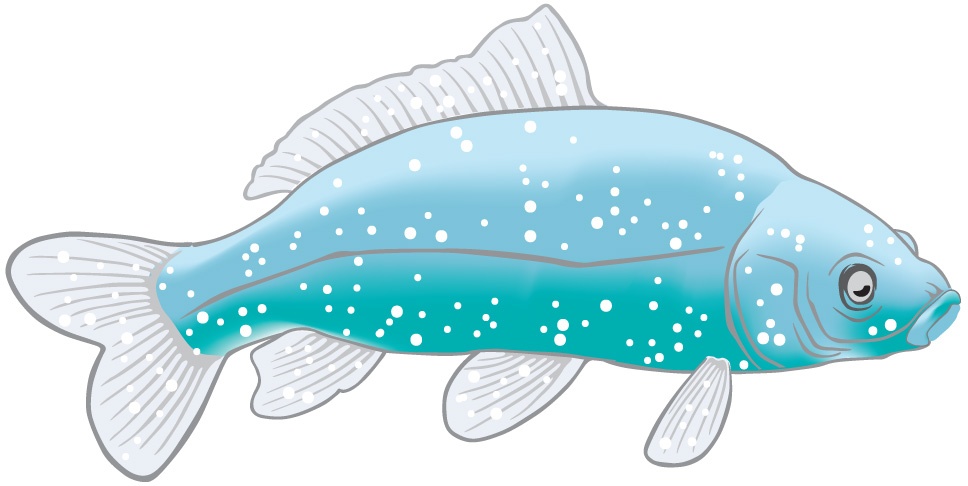

Most pathogens, bacteria, parasites, fungi, toxins and viruses, share the same environment as animals and are capable of causing disease at any time but are prevented from doing so by physical barriers of the host. Skin, scales and mucus are physical barriers to disease. In a healthy fish, these physical barriers are intact and ward off invasion by disease-causing organisms. Under prolonged stress, however, these physical barriers break down and disease organisms begin to penetrate tissues and disrupt normal cellular activity. Once a fish’s natural defenses are compromised and metabolic reserves are depleted, the normal inflammatory and antibody response to the invading organism is lost and the fish succumbs to disease.

All animals, including fish, have the ability to fight infection by antibody production. Antibodies are proteins released by cells in the fish’s body as a defensive response to the presence of foreign material. This defensive reaction to pathogenic proteins, enzymes, etc., is known as the immune response. Resistance builds as the fish is exposed to new pathogens and its body fights and suppresses the offending pathogens. Antibodies remain in the body and are activated each time the invader returns. Under prolonged stress, the fish’s normal immune response is compromised and its antibodies are less effective at eliminating the pathogens leading to full outbreak of disease and possibly even death.

The protective mucus on the fish’s body is a significant barrier to disease organisms and during periods of prolonged stress, breakdown of the mucus layer proceeds rapidly. This mucus, which also covers the internal organs, is rich with enzymes and antibodies which can eliminate many pathogens. Scales and skin below the mucus layer are secondary barriers to invasion by pathogens, parasites and toxins. Capture, netting and shipping disrupts the integrity of these important barriers facilitating invasion by opportunistic parasites. Internal barriers to pathogens also exist at the cellular level. Receptors on the cell surfaces act as barriers to environmental, bacterial and fungal toxins.

Despite the sophisticated external and internal barriers to infection, fish do get sick and it becomes necessary to medicate for disease. Unfortunately, disease in fish is difficult to determine in the early stages when treatment might be more effective. Medications are introduced once symptoms are obvious either from behavioral changes or visual recognition of disease conditions. The fish may exhibit symptoms of a single disease but frequently may become host to secondary attacks by other pathogens, i.e., a bacterial infection followed by a fungal infestation.

Medications interrupt the disease cycle giving the fish time to rebuild its immune system and fight the attack should it occur again. The disease itself is a serious source of stress and so is, unfortunately, the medication process. Ongoing illness may indicate one or several other problems in the tank or pond, specifically water quality from lack of filtration or water changes, overcrowding, incompatibility or poor diet. Many broad-spectrum and multi-use medications are available to treat these infections and produce good results if the diseases are caught early enough. Select and administer medications carefully.

Prevention

A certain amount of stress in captive fish is unavoidable. The fish most readily available in aquarium shops are those species with good track records of recovering from the stress of capture, shipping and holding. Good dealers make the investment in quarantine systems for holding and observing new arrivals to relieve stress and watch for disease.

Reputable shippers and dealers make every effort to reduce stress and these efforts should be continued once a fish has reached its final destination. Most important, understanding stress, its progression and its consequences are the best medicine. Good management to minimize stress, such as monitoring water quality, compatibility, sanitation, consistency, is always better than treating dying fish.

As with any pet, we have the opportunity to participate in a fish’s life and along with that opportunity we must be willing to accept a certain amount of responsibility for that animal’s well being and provide a well managed, stress-free environment that encourages survival.

Freshwater Fish Disease and Treatment

Freshwater Fish Disease and Treatment The Freshwater Planted Tank Product Selection & How to Guide

The Freshwater Planted Tank Product Selection & How to Guide